The Telegraph Obituary of E. Gene Smith

July 21, 2011 4:30 pm UTC

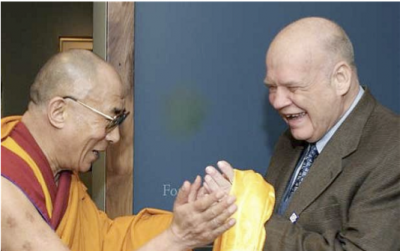

Gene Smith, who died on December 16 aged 74, was long regarded as the most knowledgeable of all Western scholars of Tibet and as the person who almost single-handedly ensured the survival of Tibetan literature.

6:36PM GMT 07 Jan 2011

Smith had travelled to India in 1965 to carry out research for a doctoral thesis on Tibetan literature, one of the most complex and extensive written cultures in the world. But by the time he arrived many dpe cha – the long, rectangular woodblock prints wrapped in cloth that are Tibetan books – had been lost or annihilated following the Chinese invasion of Tibet 15 years earlier. Instead of writing a thesis about the Tibetan corpus, Gene Smith devoted his life to recovering it, one volume at a time.

At the time of his arrival in the region, Communist Party zealots were roaming the Tibetan countryside, destroying the monasteries that served as Tibet's libraries, printing presses and schools, and looting their statuary and art, and burning many books.

Six years previously, however, the Dalai Lama and 80,000 other Tibetans had fled across the Himalayas to the safety of India and Nepal, carrying with them dpe cha that in many cases they regarded as their most precious possessions. Smith took it upon himself to trace copies of whatever works of Tibetan literature remained. He was armed with a list of the most important works in the Tibetan corpus, given to him before he left the United States by a famous Tibetan lama-scholar, Deshung Rinpoche, who had been brought by the Rockefeller Foundation to Seattle in 1959 to help in the teaching of Tibetans there.

In India, Smith learnt of other crucial texts from exiled lamas and scholars and gradually was able to locate rare and precious manuscripts. To these he was able to add copies already held in existing libraries in the remote, often tiny, hermitages and monasteries on the southern side of the Himalayas. By 1985, when he left India, he had amassed a collection of some 12,000 volumes, widely considered the largest and most important of its kind in the world outside China.

But Smith was not interested in collecting: what mattered to him was the distribution of knowledge. His genius was to find a way to reproduce these works and to place them in institutions where they would fuel future knowledge and understanding.

He found his solution in an arcane project run by the Library of Congress known as the Public Law 480 programme, through which the American government dispensed excess grain supplies to India and received notional payment in the form of culture, such as books.

In 1968 he had joined the New Delhi office of the Library of Congress as a consultant, and by 1980 had risen to become Field Director of its South Asia office. The programme allowed him to purchase Tibetan books from the refugees and to print copies – usually 20 or so – which he and his team then shipped to research institutions in the United States.

This meant that by the late 1970s the leading universities had libraries containing between 4,000 and 8,000 Tibetan texts, covering not just religion and philosophy, but also art, medicine, astronomy, history and biography.

This more than anything made possible the flourishing of advanced Tibetan studies in the United States and the world beyond. The leading Tibetan scholar, Tulku Thondup Rinpoche, told the Buddhist journal Buddhadharma in 2002 that Smith's work had "saved countless endangered texts", and Leonard van der Kuijp, professor of Tibetan studies at Harvard, described Smith as having "single-handedly put Tibetan studies on the map... Tibetan literary culture was one of the most prodigious in the world. Gene has been instrumental in keeping this alive."

As a sideline Smith wrote introductions to the copied texts which far outstripped existing Western knowledge of Tibetan literary history and rapidly acquired cult status among academics. Since there were no specialist libraries available, and he had only a day or two to write each piece, Smith relied for many of these essays on his own notes and on his prodigious memory – it was rumoured that he had photographic recall of hundreds of pages of Tibetan text.

Ellis Gene Smith was born at Ogden, Utah, on August 10 1936, to a family of devout Mormons reputedly descended from the brother of the founder, Joseph Smith. Gene showed early signs of initiative by selling fudge ice lollies while still at school.

He was formidably intelligent as well as enterprising, and went on to study at small colleges in the north-west of the United States and at the University of Utah before turning to Asian studies at the University of Washington in Seattle in 1960. There, studying with Deshung Rinpoche and other masters who had escaped from Tibet, he became fluent in both colloquial and classical Tibetan.

In 1964 he travelled to Leiden in Holland for advanced studies in Sanskrit and Pali (the language of the earliest Buddhist scriptures) before winning the fellowship from the Ford Foundation which enabled him to go to India a year later.

Copyright 2010 The Telegraph of London